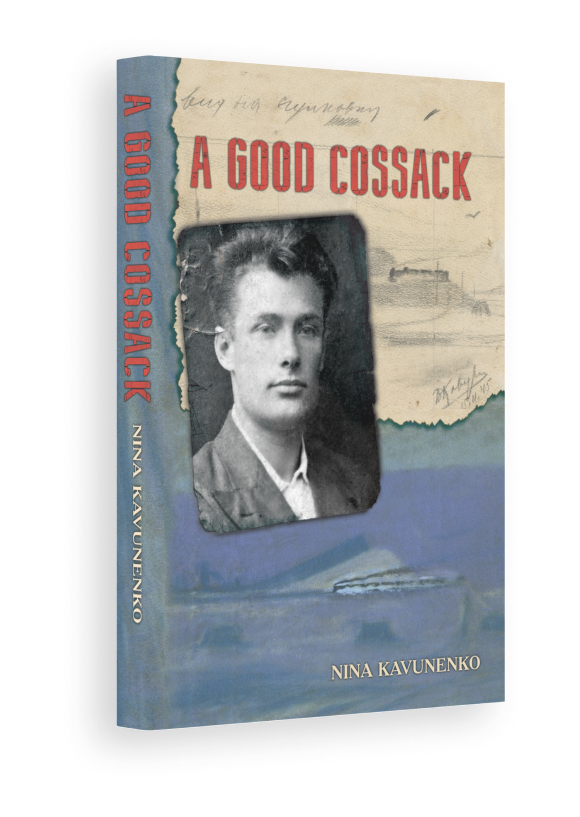

A Good

Cossack

The new biography, A Good Cossack by Nina Kavunenko is available now for purchase worldwide.

“To be a good Cossack,” his grandfather said, “you must be brave and honest. Wherever you are, you must find yourself and take command of the situation. Find a place for yourself, and then give a hand to others.”

It is 1925 in Towmach, a village south of Kiev in the Ukrainian SSR. The bitter civil war which brought the Bolsheviks to power is over now and life in the village is peaceful. Oleh’s grandfather liked to talk about the olden days and Oleh liked to listen. But how relevant would his homespun philosophy be in the days that lie before them?

When Stalin gave the order in 1928 for the immediate collectivization of all farmland, he also declared war on the peasants most likely to oppose him. He called them “kulaks” and deported them in their millions. So in early 1930, Oleh, his father and older brother were put on a crowded goods train and taken to the far north of Russia. He was just thirteen years old, and he would need all the resilience he could muster to survive the trials ahead.

As an old man living in Australia Oleh finally tells his daughter his story..

Extract

Chapter One

We were in an open space, not at a station.

Everywhere was snow. We hardly had time to look where we were when the doors were being pulled shut. Others from the train were already on the ground; we were moving along in a struggling crowd, wading through the snow. Someone was leading us—I didn’t see them, no uniforms or anything. As we floundered along I was aware of people still jumping from the train, when they were called to. I didn’t look back, didn’t even notice the train leaving. It was just gone, and we were alone in the snowy night. It was very cold, suddenly being outside. We were walking through the snow, sinking up to our knees in it.

Someone was leading us and so we walked. Someone was leading and so we were going. As the dawn began we could see we were coming to a town, quite a big town with churches and good houses, some two-story. When we came into the town we passed a school that had written on it ‘Vologda School’. I knew that name; I had learnt in History that Stalin was exiled to Vologda by the Tsar for his revolutionary activities. We came to a big church with a high wall around it and stopped at the gate. In front of the gate there was a pile of food bundles lying in the snow. One of those leading us said, ‘throw all the food here’, but I didn’t do that, I just threw some. I shook my head at Volodya, and he did the same, keeping the food hidden in his clothes. Then we were moving through the gate, a big iron gate, and into the yard, going straight into the church. When we came into the church it was so cold, the frost of winter held in its brick walls. We could not breathe—such cold!

So people came in, like sheep into the barn. Before us were bunks, built against the side and back walls, enough to sleep hundreds of people. There was nothing else, just bunks—and these were only boards in rows, no blankets or pillows. We just stood there looking about us, up into the vault of the cupola, up at the high pretty windows. Then people went over and claimed a space for themselves, started putting their things on the bunks, whatever they had. Volodya and I found ourselves a place near Anna Kozel and her two children, putting our things on a bottom bunk. There was soft and hushed talking for a while as everyone moved about. Then all became quiet. Quiet. Then someone starts to cry. The people start to cry.

Extract

Chapter Seven

I wonder if he blamed the regime that governed through fear, that made him so afraid of being asked about himself. ‘What point to blame the government?’ he said. ‘If you show anger and criticize you will not survive. You will not live.’ But inside, in your thoughts, were you not critical? ‘Even in my mind I must not waste time criticizing. I just had to accept the situation and try to survive.’ But after what happened in the village, your family cast out as enemies … ‘I had to accept what happened. I did not think about being sent to Siberia. I even forgot about that—out of my mind to tell anything!’ I know I should drop this, I know it’s upsetting, but I’m trying to understand.

I remind him of the purges, of people he saw starving. How could he not criticize that? ‘In that way I did not accept. If possible, I would not say if I saw something, I just let it pass—like when I had to check the documents of people coming to the state farm.’ ‘So you did not entirely accept the system,’ I say. ‘If you could you would go against it.’ ‘Perhaps yes, in some small way. But if I was to say I was working against it and criticizing, no one who had been there too would believe it. If you try to put it like that they would laugh at you.’

I’d never realized how deep this went. I’d always assumed he felt wronged, unmoved by the Party propaganda. Clear-eyed and detached. In later life he would speak passionately against Communism, even protesting outside the Russian Embassy. But back then he didn’t feel aloof; he felt unsafe and tried to conform. ‘I grew up with those slogans,’ my father said. ‘You remember how I marched as a child, past my father’s shop? Demonstrating against Capitalism and all that? Well that’s how it was … Even my father on the train to Siberia was saying he should have paid more attention to the politics, so we would not have been Enemies of the People.’

We both fall silent. I’m about to suggest we take a break when my father begins to speak. ‘People just tried to survive in a brutal regime and it was not an issue to wonder who to blame. You had no real idea of who are “they” causing this misery.’

GALLERY

Paintings by Oleh’s brother, Volodya Kavunenko

Recollecting the Past, 1971

Midday, 1972

Untitled, 1976

Untitled, 1980

Untitled, 1980

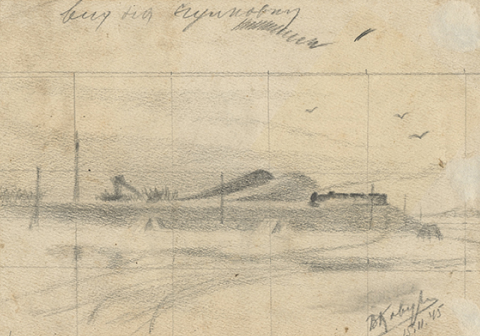

View at Chulkovka, 1945

The Author Arrives at Towmach Village 2007

CONTACT

For all media and other inquiries